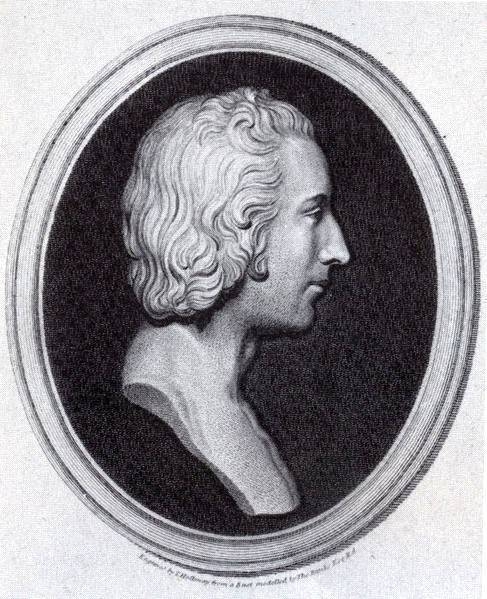

Thomas Muir of Huntershill, by Ian Callendar, after the Holloway engraving of the lost bust by Thomas Banks R.A. Thomas Muir of Huntershill 1765-1799 M. DONNELLY ©Michael Donnelly 1975 (reproduced with kind permission of Michael Donnelly 2009) CONTENTS Preface Foreword by Oliver Brown Early Years Education Graduation Expelled from University Patronage: The Landlords v. The People Revolution in France Muir and the United Irishmen Public Enemy No. 1 Transportation The Third Convention Arrival in Australia Escape to America Return to Europe The Last Days in France Bibliography PREFACE This short pamphlet represents a biography of the eighteenth-century Scottish radical and nationalist, Thomas Muir of Huntershill. It is aimed specifically at the casual reader who wishes to have the essential facts of Muir’s career in a handy brochure format and it is published to coincide with the opening of a small museum within Huntershill House, Muir’s home. I wish to thank the authorities of the National Maritime Museum, London, The Royal Scottish Society of Antiquaries, The Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh, the Mitchell Library, Glasgow, and the Glasgow Art Gallery and Museums, for permission to use the illustrations reproduced in this volume. Particular thanks are also due to Ms Unity Miller for essential assistance in typing the manuscript, to my old friend Ian Callender for providing the excellent sketch of the missing portrait bust of Muir by Thomas Banks R.A. and to Dr J. A. Russell for his kind assistance and interest in the production of this brochure. And last but not least, I should like to thank Mr Oliver Brown for writing the foreword and for his kind assistance in translating many manuscripts, thus making this publication possible. M.D. FOREWORD If politics is the art of achieving the possible, it involves some sacrifice of principle. The danger is that one compromise makes the next unavoidable and the revolutionary finally ends with a seat in the House of Lords. There are, however, some people who refuse to compromise because they represent ideals which seem absurd only because their time has not yet come and might never come but for these heretics. They are generally regarded by their contemporaries as fools or criminals - often as both. Such was the Bishopbriggs lawyer, Thomas Muir, who, with his legal training and proved ability, might reasonably have been expected to sit on the Judicial Bench instead of being sentenced by it to imprisonment in exile. He ruined a promising career by a complete disregard for his own interests - which is never regarded by a man’s neighbours as a sign of common sense. Only the French recognised his political sagacity by choosing him as a Minister of the Scottish Republic which they intended to set up; for Muir was just as enthusiastic a Scottish nationalist as he was a citizen of the world. Every generation asserts the right to overturn the judgement of previous generations. We honour Queen Mary rather than her executioner, Elizabeth; Prince Charles rather than his victor, Butcher Cumberland, and we deny to the victorious King Robert some of the honour due to him in order to give it to the National Martyr. Today the Honourable Lord Braxfield is regarded as a silly old man with infantile illusions. On the other hand the heresies of Thomas Muir no longer interest us because they are commonplace, however imperfectly we apply them. In this we fail to recognise the enormous progress which we have made, morally and intellectually, in this change. To Muir we owe an unacknowledged debt. He sought, like all great men, to attain the unattainable, knowing that the alternative is to bear the unbearable. He has joinedOliver Brown “The Choir invisible of those immortal Dead Who live again in minds made better by their presence.’ May his life have that effect on ours! EARLY YEARS Thomas Muir, the Scottish Republican and Revolutionary, was born in Glasgow on the 24th August 1765. His father, James Muir, was the son of the ‘bonnet laird’ of Hayston and Birdston farms near Kirkintilloch. As a younger son James Muir had little prospect of inheriting his father’s property. His family, however, had in Maidstone, Kent, relations who were prosperous hop-growers and it was towards this branch of trade that young James was persuaded to direct his energies. In this business venture he achieved considerable success and by the time of his marriage in 1764 he was firmly established as a hop-merchant in the High Street of Glasgow. Here, in the heart of the town’s ancient University quarter, he settled with his wife, living in a little fiat above his shop. By all accounts Muir senior was a man of some education, whose interest in commerce extended far beyond that of his fellow businessmen, for he has been credited with the author ship of a pamphlet on ‘England’s Foreign Trade’. By the 1780s he reached the summit of his social aspirations when he purchased the property of Huntershill House , together with adjoining lands. Of Muir’s mother, Margaret Smith, nothing of a biographical nature has been recorded. However, we do know that both Muir’s parents were orthodox Presbyterians, consequently young Thomas’s early upbringing was very much within the confines of the rigid moral and social ethic of ‘Auld Licht’ Calvinism. Thus, early accounts describe him, not unnaturally, as ‘a pious child of modest, reserved nature’. EDUCATION Muir’s education began at the age of five when his father acquired the services of William Barclay, a local schoolmaster, as a private tutor. A conscientious, rather than a brilliant pupil, Muir made steady progress and in 1775 at the early age of 10 was admitted to the ‘gowned classes’ of Glasgow University. After attending classes regularly for 5 sessions he matriculated (1777) and at the desire of his parents embarked upon a study of Divinity. His religious convictions, both at this time and throughout the remainder of his life, were sincere and uncompromising. Like his parents he was a zealous supporter of the ideals of the ‘Auld Licht’ or popular party, in Kirk politics. As the only son of increasingly wealthy parents he wanted for nothing. He had discovered a natural flair for foreign languages, and in furtherance of this interest he was soon the owner of a ‘valuable and extensive library’. GRADUATION In 1782 at the age of 17 Muir graduated M.A. It was at this important stage of his education that he became increasingly influenced by the teachings of John Millar of Millheugh, Professor of Civil Law. Having attended several of Millar’s classes he developed such a passionate interest in the subject that he thereafter abandoned his studies for the Church. At the beginning of the 1783-4 term he applied, and was accepted, as a student in Millar’s classes on Law and Government. Chiefly remembered as a pioneer of sociology, John Millar was throughout his long professional career regarded as the supreme public lecturer in Scotland. The former pupil and protégé of Adam Smith, David Hume and Lord Kames, Millar had raised the stature of his Chair from obscurity to inter national fame. His course of lectures on Law and Government (the latter being the first of its kind in Europe) drew students like a magnet from as far away as Russia and America. In politics Millar was a Republican Whig and one of the most scathing critics of the so-called ‘benevolent despotism’ of Henry Dundas. As an intellectual leader of the Scottish Whigs his chief objective throughout his long professorship was to maintain a constant attack upon the nerve centre of Scottish political conservatism in the Faculty of Advocates. This he sought to accomplish by a regular transfusion of young Whig advocates skilled not only in the letter of the law, but also imbued with a due reverence of its spirit. His legendary capacity for drawing forth the hidden talents of’ his pupils seems to have worked wonders upon Muir. The shyness and reserve formerly noted were now rapidly dispelled. He entered into the spirit and bonhomie of the various students’ clubs and societies in which the major topics of the day (American Independence, Patronage, and Burgh Reform) were hotly debated. EXPELLED FROM UNIVERSITY Unfortunately for Muir this most fruitful episode in his University career was soon to be abruptly terminated. In May 1784 a violent dispute occurred between Professor John Anderson and other members of the Faculty, including Principal Leechman and Professors Richardson and Taylor. The occasion of the dispute was the refusal of a majority of the Faculty to minute several complaints of the Professor regarding the alleged abuse of college funds, etc. Anderson’s comments upon being informed that his complaints were being omitted from the record as ‘extraneous and indecent’, were uncomplimentary enough to provoke the Faculty into voting his suspension from the privileges of the Senate. Today, Professor Anderson’s chief claim to fame rests upon his advanced ideas on the subject of Adult and Technical Education and his posthumous foundation of the Andersonian College (now Strathclyde University) as a rival to Glasgow. His institution of what he called ‘anti—toga’ classes, whose doors were thrown open to the small craftsmen and artisans of Glasgow, earned him a widespread popularity among both students and general public. This popularity not unnaturally aroused the jealousy of his less charismatic associates. Seeing that redress and reform were unobtainable at the hands of the Faculty, Anderson petitioned the Chancellor, the Marquis of Graham, and Henry Dundas, the Lord Advocate, for assistance in procuring a Royal Commission of Enquiry into the University’s affairs. Both, however, refused to interfere in the dispute. Nothing daunted, Anderson returned from the summer vacation of 1784 and announced his intention of submitting similar petitions to the Secretary of State in London. In the campaign which now commenced, Anderson received widespread support from the citizens of the town and from the University students. The climax to this heated dispute came on the 24th February 1785 when the Glasgow Trades, by a large majority, voted in support of Anderson’s cause. However, a few days later, as a result of an impassioned appeal from the aged and infirm Principal Leechman, this vote was dramatically reversed. The senior students, particularly the M.A.’s who had been so active on Anderson’s behalf, responded by issuing a pamphlet entitled ‘A Statement of Fact’, in which Leechman and the Faculty were unceremoniously debunked. The embattled Faculty, outraged by what they regarded as an act of gross insubordination, were quick to retaliate. Thus, as soon as the indefatigable Anderson had departed for London, disciplinary proceedings were launched. An ultimatum was posted in all college lecture rooms naming Muir, McIndoe, Humphries and ten others as ringleaders. An immediate ban was enforced upon their attendance at lectures prior to the result of hearings. Muir and his fellow students in accordance with the principles instilled by Millar, requested legal representation at the hearings. This request was contemptuously rejected, whereupon Muir gave notice of his voluntary self- expulsion from the University. His fellow students, who decided to make a fight of it, were not so lucky. McIndoe was expelled along with one William Clydesdale, while Alexander Humphries, co-author of the offending pamphlet, was not only expelled, but also deprived of his degree, an exceptionally vindictive act. Muir’s champions on the academic staff however, were not prepared to see his career destroyed for actions clearly dictated by principle. Thus at the beginning of the new academic year, Muir with the assistance of Professor Millar, obtained a place at Edinburgh University under the Whig Professor of Law, John Wylde. Here he completed his studies and having passed his Bar examinations was admitted to the Faculty of Advocates in 1787 at the age of 22. PATRONAGE: THE LANDLORDS v. THE PEOPLE Those that may have thought that after the notoriety of his abrupt departure from Glasgow University, Muir would choose a life of quiet respectability, were soon to have their illusions shattered. As an Elder of the Church of Scotland for his home parish of Cadder, he became embroiled at the beginning of 1790 in bitter dispute with the local landlords led by James Dunlop of Garnkirk, a rich coal owner. Muir acting on behalf of the elders challenged the attempt of the landlords or heritors to pack the selection committee for a new minister with ‘Parchment Barons’. Upon the case being referred to the Synod at Glasgow, Muir was appointed as Counsel for the congregation and fought a bitter and protracted case on their behalf all the way to the General Assembly. In the event the case of the landlords was thrown out and Muir and his party emerged victorious. In legal circles and beyond, Muir quickly acquired a reputation as a man of principle, prepared to take on the most unrewarding and difficult cases and even occasionally foregoing a fee when petitioned by a destitute client. His outspoken conviction that many existing laws were criminally biased against the poor, won him the respect of the younger advocates who nicknamed him ‘the Chancellor’. His views on law reform were however anathema to the ogres of the High Court, Lord Braxfield and Lord Advocate, Robert Dundas. REVOLUTION IN FRANCE The French Revolution of 1789 revived the hopes of all members of the Whig party in Scotland and England, in their campaign for burgh and county reform. However, as the Revolution progressed and England witnessed the emergence of popular reform societies advocating Parliamentary reform, the aristocratic section of the Whigs began to fear the spread of revolutionary ideology on to home territory. It was in an attempt to forestall such a development that the younger generation of Foxite Whigs in Parliament and the Lords inaugurated in April 1792 the London Association of the Friends of the People. Led by the Scots Lords, Lauderdale and Buchan, this society enjoyed widespread initial support from leading Whigs throughout Britain. Since 1789 many clubs and societies had sprung up in the principal towns and villages of Scotland in support of the Revolution and its principles. In June 1792, the members of these societies and, in particular, those at Glasgow, Edinburgh, Dundee and Perth, began a regular correspondence with the object of forming a Scottish counterpart to the London Association. By the end of June 1792, a plan of organisation, principally drawn up by Muir and William Skirving, a Fifeshire farmer, was set in motion. In distinct contrast to the London Association, which was deliberately exclusive, Muir and his associates, taking into consideration the vital educational differential between the working people of Scotland and England, opted for a nationwide association of reform clubs unlimited to any social class. After some initial difficulties due to the entrenched opposition of Henry Erskine, the Dean of the Faculty and leading Scottish Whig, the Scottish Association of the Friends of the People was duly formed at Edinburgh on 26th July 1792. Supported by two new publications, the Edinburgh Gazeteer and the Caledonian Chronicle, plus James Tytler’s Historical Register, the new movement rapidly expanded. MUIR AND THE UNITED IRISHMEN As early as September 1792, acting upon his own initiative, Muir began a correspondence with Archibauld Hamilton Rowan, Secretary of the United Irishmen. In this correspondence Muir detailed the aims and objectives of the association and suggested a closer unity of action between the two movements. Other activities during this period included the formation of the Glasgow society (3rd October) and a propaganda tour of Stirlingshire, Dunbartonshire, and Renfrewshire. As a result of this tour new societies were formed at Kirkintilloch, Birdston, Lennoxtown, Campsie and Paisley. Upon the 21st November, Muir, having been elected Vice-President of the movement at the Edinburgh monthly meeting, called for a General Convention of the societies to be held there in December. On the 8th December, as the first of the delegates were arriving in the capital, an Address of Fraternity from the United Irishmen arrived at Muir’s lodgings in Carrubers Close. Drawn up by Dr Drennan of Belfast, its nationalistic sentiments and appeal to the independent spirit of the Scottish people were entirely to Muir’s satisfaction. However, he appears to have unwisely circulated a copy of it among the delegates prior to the first sitting of the Convention. Consequently when during the first session Muir rose to present the Address he was vigorously opposed by a powerful unionist section among the delegates led by Col. William Dalrymple, Lord Daer and Richard Fowler. Their ground of protest was to the effect that the Address contained ‘Treason or Misprison of Treason against the Union with England’. Lord Daer in particular was against the document either being accepted or even read to the Convention. This attempt to silence Muir was, however, overwhelmingly opposed and although the Address ‘in its original form’ was ultimately rejected, Muir obtained permission to read it over and ended by declaring to the Convention, ‘We do not, we cannot, consider ourselves as mowed and melted down into another country. Have we not distinct Courts, Judges, Juries, Laws, etc.?’. To this Richard Fowler protested ‘that Scotland and England were but one people’. Some four weeks later Lord Daer, in correspondence with Charles Grey of the London Friends of the People, candidly admitted that ‘the Friends of Liberty in Scotland have almost unanimously been enemies to the Union with England. Such is the fact, whether the reason be good or bad.’ PUBLIC ENEMY No. 1 With the ending of the Convention Muir became a marked man; a government spy had successfully penetrated their security and had turned in a full account of their proceedings with particular emphasis on the controversial Irish Address. Muir, apparently unaware of the net that was closing around him, busied himself in the days following the Convention with preparing his brief as defence counsel for James Tytler who had been arrested on a charge of sedition the previous month. Meanwhile Lord Advocate Robert Dundas initiated an intensive investigation of Muir’s movements during the previous three months, and was soon boasting to his uncle, Home Secretary Henry Dundas, that he would ‘lay him by the heels on a charge of High Treason’. Thus it was that Muir while on his way to Edinburgh on the morning of the 2nd January 1793 to attend Tytler’s trial, was himself arrested on a charge of sedition and brought under guard to Edinburgh. After an intensive interrogation before the Sheriff during which he refused to answer any questions, Muir was released upon bail. Realising that he and Tytler were to be but the first in a series of selective prosecutions against the Association’s members, Muir decided to put his time at liberty to good use. On the 8th January he set out for a brief visit to London with the intention of informing the Reformers there of the plight of the Scottish Association. It was during this visit that Muir discovered to his great dismay, the state of panic prevailing among the English Whigs over the proceedings of the trial of the French King. Far from promising aid and comfort to their Scottish allies, both Charles Gray and Lord Lauderdale were now openly considering the abandonment of the campaign for Parliamentary reform. It was against such a background of despondency that Muir, in a desperate attempt to prevent an irreversible set-back to the reform movement, left London for France in an eleventh hour bid to persuade the French leaders to spare the life of the King. His mission was doomed from the outset, for in spite of his utmost efforts he reached Paris only on the eve of the execution, by which time all hope of intervention was out of the question. As a missionary from the Whigs and the Scottish Movement, he was treated with great courtesy by the revolutionary administration. He was interviewed and feted by many of the outstanding personalities of the Convention including among others Condorcet, Brissot, Mirabeau and Madame Roland. While in Paris he also met Thomas Paine and Dr William Maxwell of Kirkconnel, the future doctor and associate of Robert Burns. With the outbreak of war with France the anti-reform party in Scotland became increasingly militant, and Dundas sensing that the time was ripe, advanced the date of Muir’s trial from April to 11th February. On being informed by letter of this manoeuvre, Muir, realising the impossibility of returning to Edinburgh in time, drafted a letter to the press stating his intention to return as soon as passport difficulties would admit. Dundas, of course, was not interested in any declarations of intent and immediately set in motion the legal steps required to ensure Muir’s outlawry for non-appearance. This was done on 25th February 1793 when Lord Braxfield pronounced him a fugitive from justice. TRANSPORTATION Henry Erskine, who had not forgiven Muir for his attempts to undermine his authority with the burgh reformers, was now presented with the perfect opportunity for revenge. On the 6th March he convened a meeting of the Faculty of Advocates at which Muir, with no one to speak in his defence, was unanimously expelled and his name struck from the register. It was not until the end of June that Muir finally obtained a passage from Havre de Grace in an American ship, The Hope of Boston. Disembarking at Belfast where the ship had docked to pick up cargo, Muir made his way south to Dublin where upon consulting the United Irishmen at their Taylors Hall headquarters, he was sworn in as a fully fledged member of the Society. After spending a week at the home of Archibauld Hamilton Rowan at Rathcoffey, Muir decided to return to Scotland via Belfast and Donachadee. On the 24th August 1793 (his 28th birthday) Muir landed at Portpatrick and was almost immediately recognised by one Cunningham, a Customs Officer, and placed under arrest. Brought under heavy guard to Edinburgh and incarcerated in the notorious Tolbooth prison Muir now became the chief victim in a series of ‘Show’ trials aimed at smashing and demoralising the Scottish movement. The circumstances of this trial before Braxfield , the Jeffries of Scotland, and a hand-picked jury of militant anti-reformers, has passed into legal history as a classic example of the political abuse of the judicial process. Yet, in spite of Braxfield’s vindictive ferocity and the unprecedented sentence of 14 years transportation, Muir’s manly conduct and fiery oratory were so impressive that the entire effect of the trial misfired. The movement had found in Muir their first martyr, and instead of disintegrating, actually stiffened their resistance to Government coercion. Against such a background, Muir’s continued presence in Edinburgh was regarded as a serious threat to public order, and he was removed to an armed cutter, the Royal George, at Leith Roads. There he was soon joined by the Revd Thomas Fyshe Palmer , who had received a sentence of 7 years transportation in similar circumstances at Perth. Skirving, now fighting a dour battle to keep the movement in fighting trim, resolved to present the Government with a united front in the form of a new Convention, better organised and more representative than its predecessors. Dundas reacted to this new challenge by ordering the immediate removal of Muir and Palmer to the Hulks at Woolwich prior to their departure for Botany Bay. THE THIRD CONVENTION The third Convention of the Friends of the People and its successor the ‘British Convention’ were however, like their predecessors, largely dominated by the delegates of the Edinburgh Societies. Moreover, by means of arrests and desertions, the Scottish movement had been deprived of most of its articulate leadership. Into this vacuum stepped three English delegates, Maurice Margarot, a merchant with a university education, Joseph Gerrald , friend and correspondent of William Godwin and an orator of flawless eloquence, and Matthew Campbell Browne, an actor turned reformer. After the early departure of Lord Daer, who was already suffering from the tuberculosis which was to lead to his premature death the following year, these three talented yet wholly injudicious men came to dominate the Convention and its proceedings. Only they and Muir realised the true nature of the extra ordinary organisational differences existing between the reform movements in England and Scotland. Where the English societies remained psychologically and geographically divided, the Scots had an unprecedented degree of national unity backed by the general sympathy of the common people. Finding them selves almost by accident at the head of such an organisation, they threw all discretion to the winds. Urged on by Campbell Browne’s wild histrionics, the movement’s covert aims now became an open secret. Apeing the Convention at Paris, the terms Citizen President, Secretary General, etc. were now introduced into its published reports, while the Convention was rechristened the ‘British Convention’. What Muir thought of this reckless exposure to destruction of the organisation which he and Skirving had so carefully nurtured is revealed by his description of it in 1797 as ‘a miserable plaything of the English Government’. Ultimately it was a motion of Charles Sinclair, delegate from the Society for Constitutional Information (London), which gave Dundas his much sought-for excuse to disperse the Convention. Commenting upon the Convention Bill recently passed in Ireland as a means of suppressing public assemblies, Sinclair moved that a secret committee of four, together with the Secretary, be invested with the power to fix the meeting of a Convention of Emergency. This Convention would if necessary declare itself permanent and resist attempts to disperse it. When the diligent spy, ‘J.B.’, duly delivered his report of this discussion the authorities moved swiftly. Early on the morning of the 5th December arrest warrants were issued and served by armed bailiffs upon Skirving, Margarot, Gerrald, Sinclair and Matthew Campbell Browne. In the trials which followed Skirving, Margarot and Gerrald were each respectively given sentences of 14 years transportation. While these and other disasters were befalling the Scottish Movement, Muir and Palmer were languishing in the prison hulks by night and being forced to labour in a chain gang on the banks of the Thames by day. An attempt to ship them out to Botany Bay in the convict transport Ye Canada had failed, when in true ‘coffin-ship’ tradition, her timbers were found to be rotten. After spending some time in Newgate Jail where they were joined by the newly convicted associates, Skirving and Margarot, they were removed by coach to Portsmouth and placed aboard a new transport The Surprise. In spite of belated and somewhat reluctant attempts on behalf of the Whigs in Parliament and the Lords to obtain a pardon for the radicals, they were abruptly shipped out for Botany Bay on the morning of the 24th May. ARRIVAL IN AUSTRALIA During the long voyage out to Australia an attempt was made (with or without official connivance) to discredit Muir, Skirving and Palmer by implicating them in an alleged mutiny led by the first mate. This affair, however, was so badly bungled that, in spite of having to endure much harsh and brutal treatment at the hands of the captain, the reformers had little difficulty in refuting the evidence against them upon arrival at Port Jackson. Muir’s term of confinement at the penal colony appears to have been pretty uneventful. As political prisoners, and men of talent and education, he and his associates were accorded far greater freedom of movement than ordinary convicts. Prior to their departure from Portsmouth each had received a considerable sum of money raised as a subscription on their behalf among the wealthy London Whigs. By this means they were able to sustain themselves without recourse to the official colonial stores, and thereby keep free of the compulsory manual labour normally demanded from all dependents. By December all four had spent the bulk of their remaining cash in purchasing plots of land. Skirving and Muir both seem to have acquired the services of some time-served convicts as servants. Palmer purchased 100 acres of land for £84, and was soon waxing eloquent about his new occupation as a farmer. Unlike his companions, or indeed his father, Muir had little or no taste for farming and with an eye to ultimate escape from the settlement, he purchased a small hut and several acres of land on the opposite side of the bay. By this means he was able to remove himself from the direct observation of the Governor and his soldiers and at the same time was provided with a legitimate excuse for keeping a small boat. Early in 1796 with the assistance of François Peron, a French explorer and naturalist, he succeeded in arranging his escape from the settlement on board the American ship the Otter of Boston. The captain of this vessel, Ebenezer Dorr, had, how ever, made it a precondition of his part in the escape plan that Muir and any who chose to go with him should effect their own escape from the harbour at Port Jackson, as this was carefully guarded by a blockading frigate. Muir swiftly contacted his fellow prisoners. However, in the event, none but himself was able to go. Skirving who had suffered from a recent bout of yellow fever was too weak, and would shortly be dead. Gerrald who had recently arrived in the settlement was in the final stages of acute tuberculosis and the Revd Palmer, who was nursing him, refused to leave his charge. Only Margarot might have availed himself of Muir’s plan; however he was absent at a farm deep in the hills at Parramatta, and in any case he had been sent to coventry by his former colleagues because of his part in supporting the mutiny allegations. ESCAPE TO AMERICA On the evening of the 17th February 1796, Muir together with two convict servants, loaded up his small boat with one day’s provisions and stealthily rowed their way out of harbour. Hugging close to the shore they successfully eluded detection by the watch on the frigate and navigated their way towards their prearranged point of rendezvous. About 12 am. on the following day, wet and exhausted, they were hauled aboard the Otter. Muir, who had been unable to bring with him any of his personal property, left behind a note gifting his books and papers to Palmer, with whom he also left a letter for the Governor thanking him for his tolerance and stating his intention of practising law at the American Bar.After a highly adventurous voyage across the as yet largely unchartered Pacific to Vancouver Island, the Otter finally dropped anchor in Nootka Sound on 22nd June 1796. In conversation with Don Jose Tovar, the pilot of the Sutil a Spanish inshore patrol vessel at anchor in the Bay, Muir learned to his dismay of the presence in neighbouring waters of the Providence, a British Man o’ War. This vessel had visited Port Jackson shortly before Muir’s escape and, since he had almost certainly become acquainted with the captain or members of the crew, his life was now in real danger. To be captured while under sentence of transportation meant immediate execution. Once again Muir’s extraordinary luck held out. While a student at Glasgow, he had acquired a fluent command of Spanish and he was now able to persuade Captain Tovar to break his regulations regarding the admission of foreigners into Spanish Territory. Changing vessels he sailed with Tovar down the coast of California to the port of Monterrey. On arrival at this important Spanish outpost, Muir was introduced to the Governor, Don Diego Borica, who was favourably impressed by his character and intelligence, and allocated him accommodation along with his own family in the Presidio. However, when Borica in due course submitted a report on Muir to his superior, the Viceroy at Mexico City, matters took a turn for the worse. Ignoring Muir’s request to pass through Spanish territory to the United States, the Viceroy, instead, ordered the severe disciplining of Tovar for violating his orders. Muir’s use of Washington’s name and his claims of friendship with many of the leading personalities of the French Revolution, had rendered him highly suspicious to the Spanish authorities. Accordingly, Borica was directed to have Muir conducted with all haste to the capital ‘without open sign of his being under arrest’. Accompanied by two officers detached from the Governor’s staff, Muir, after a gruelling and often dangerous trek across the mountains, reached Mexico City on 12th October. For some days he was held in detention and closely questioned as to his purpose in entering California. It is evident, however, that his explanations were disbelieved by the sceptical Viceroy, who resolved to ship him out to Spain as a suspected spy. Under heavy guard, Muir was now despatched on the road for the port of Vera Cruz where he arrived on 22nd October. In spite of his demands to be put on board an American ship, he was now shipped out to Havana in Cuba to await the departure of a convoy for Spain. RETURN TO EUROPE For some time, Muir appears to have regained his liberty in this port, for he spoke to several American merchants explaining his plight. He also appears to have attempted an escape, only to be recaptured and imprisoned for three months in the dungeons of the La Principia Fortress. However Muir was nothing if not resourceful and it was while he was in La Principia that he succeeded by some means in contacting Victor Hughes, the French Agent for the Windward Islands. On learning of Muir’s situation Hughes wrote to the Directory in France, thus providing them with the first concrete news of Muir’s escape and survival. He also wrote an indignant letter to the Governor of Cuba protesting bitterly at Muir’s harsh treatment and demanding his release. However, by the time this letter arrived in Havana, Muir had already sailed for Spain. Whatever misgivings or fears Muir may have had for his safety at the hands of his Spanish jailers, there was one danger which had not occurred to him - that of confrontation with an English fleet. On the morning of the 26th April 1797 as Muir’s ship, the Ninfa, approached the entrance to Cadiz Harbour, he was confronted by several British Men o’ War who for some weeks had been blockading the port. Seeing at once that a conflict was inevitable, Muir approached the captain and asked to be put ashore as he was unwilling to bear arms against a ship which almost certainly contained some of his fellow countrymen. The captain, however, faced with the likely destruction of his vessel, had no time to consider the feelings of a prisoner. Turning about, the Ninfa and her sister ship the Santa Elena headed up the coast, hotly pursued by the British ships. After a chase of some three hours duration, the Ninfa and the Santa Elena were engaged in battle opposite the mouth of Cann Bay. In the action which followed, the Ninfa was seriously damaged, while the Santa Elena, reputedly a rich bullion ship, was deliberately scuttled by her captain. During the last few moments of the engagement, Muir received a glancing blow to the face from a piece of shrapnel which smashed his left cheek bone and seriously injured both his eyes. One of the crew under interrogation appears to have revealed the fact of Muir’s presence on board, and a careful search was made for his body. However, the Spanish captain insisted that Muir was among the dead and in the event he was so badly disfigured that his would-be captors failed to identify him, and he was sent ashore with the wounded. Now began a long painful recovery, while the French and Spanish authorities, from Consular to Ambassadorial and ultimately at Ministerial level, indulged in a bitter diplomatic wrangle over Muir’s release. THE LAST DAYS IN FRANCE Finally on the 16th September 1797 the Spanish Government relented and decreed Muir’s release and perpetual banishment from Spanish territories. Still weak and emaciated from his sufferings, Muir made his way to France by way of Madrid and San Sebastian, aided and assisted by a young officer from the French Consulate at Cadiz. In early November 1797 he arrived exhausted at Bordeaux, where he was hailed publicly as a ‘Hero of the French Republic’ and a ‘Martyr of Liberty’. Feted by the civic authorities and literary societies, his last portrait, commissioned for display in public buildings, shows him with a large black patch over his left eye. The loss of his left cheekbone had caused that side of his face to droop revealing the teeth in a perpetual grimace. Muir, weak and half blind, slowly made his way north to Paris where he arrived on 4th February 1798. His arrival in the capital was heralded by a great outburst of popular adulation. David, the great French artist and propagandist was officially appointed to welcome him to the city, in a front page eulogy in the Government journal Le Moniteur. From the very outset, however, Muir made it abundantly clear to his benefactors that, flattered though he was by their attentions towards him, it was their intentions on behalf of his suffering countrymen which were now to be his chief concern. He associated with Thomas Paine and James Napper Tandy of the United Irishmen, from whom he learned the exciting news of the near-insurrection in Scotland over the Militia Act. During 1798 he submitted many letters and memoranda to the Directory urging them to intervene militarily on behalf of the people and thus aid them in establishing a Scottish Republic. His chief confidant and informant during 1798 was Dr Robert Watson of Elgin, emissary to France on behalf of the United Englishmen. From him he learned for the first time details of the strength and extent of the United Scotsmen, the new revolutionary association which had replaced the Friends of the People. From Watson he also learned of the impending arrival in Paris of James Kennedy of Paisley and Angus Cameron of Blair Atholl as delegates of the new movement. Since Muir was by this time the principal intermediary between the Directory and the various republican refugees in Paris he was aware that his movements were under scrutiny by Pitt’s agents. Accordingly, in his last known communication with the Directory in October 1798, he requested permission to leave Paris for somewhere less conspicuous, where his crucial negotiations with the Scots emissaries could be conducted in safety. Thus it was that sometime in the middle of November 1798, Muir moved incognito to the little lie de France village of Chantilly to await the arrival of his Scots compatriots. There on the 26th January 1799 he died, suddenly and alone, with only a small child for company. So close had his efforts for security been that not even the local official knew of his presence or identity. No identifying documents or papers were found on his person and his name was discovered only when the postman remembered delivering newspapers to him addressed to ‘Citoyen Thomas Muir’. When several days later the news of Muir’s passing finally reached Paris, a brief obituary notice was inserted in Le Moniteur to the effect that he had died from a recurrence of his old wounds. ‘We have achieved a great duty in these critical times. After the destruction of so many years, we have been the first to revive the spirit of our country and give it a National Existence.’ Thomas Muir 1798. B I B L I 0 G RAP H Y 1. Thomas Muir, a sketch, William Marshall. The Glasgow Magazine, Aug.—Sept. 1795. 2. The Life of Thomas Muir, Esquire, Advocate, Peter MacKenzie. Glasgow 1831. 3. The Death of Thomas Muir, Dr Henry Meikle. The Scottish Historical Review, Vol. xxvii. 4. Scotland and the French Revolution, H. W. Meikle. Glasgow 1912. 5. Thomas Muir, Scottish Martyr, John Earnshaw. Studies in Australian & Pacific History, No. 1, 1959. 6. The Scottish Martyrs, Frank Clune. London 1969. |